Back in the USSA

A Reflection on Political Awakening, Cultural Shifts and Collective Consciousness

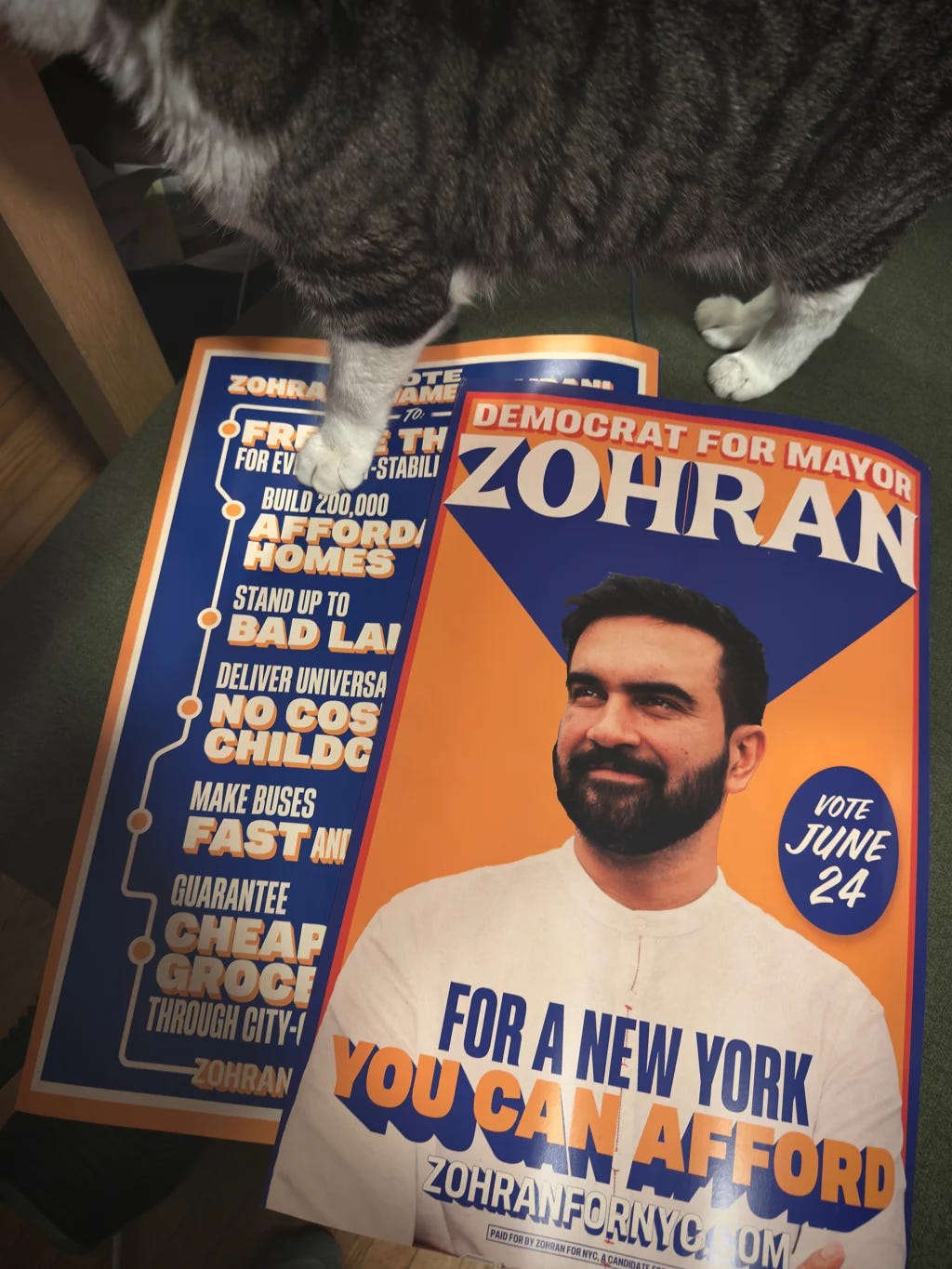

The Beatles' "Back in the USSR" has a way of lodging itself in your consciousness at unexpected moments. Flying into London Heathrow, the song's chorus played on repeat in my mind—not just as musical accompaniment to international travel, but as a soundtrack to deeper contemplations about political transformation. Perhaps it was the recent media coverage of Zohran Mamdani's victory over Andrew Cuomo that triggered this particular earworm, or maybe it was the growing sense that we're witnessing the emergence of something unprecedented in American politics.

The song itself—McCartney and Lennon's cheeky mashup parody of Chuck Berry's "Back in the USA" and The Beach Boys' "California Girls"—was once dismissed by critics as "very un-American." Lennon's response was characteristically sharp: "How observant—we are not American." There's something deeply satisfying about that kind of subversion, the way it punctures ordained dogma with the banal precision of British humor. Released in 1968 as the opening track of the White Album, the song emerged during a year that fundamentally reshaped modern history.

The Watershed Moment of 1968—and Now

1968 stands as a watershed year in geopolitics—a confluence of political, social, and cultural events that created seismic shifts in consciousness. The Vietnam War raged on, Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated, violent protests erupted in Chicago, Nixon ascended to the presidency, students protested globally, counterculture emerged, Prague Spring bloomed and was crushed, and Apollo 8 orbited the moon. It was a year of tragedy, upheaval, realignment, and profound transformation.

2025 feels like another such moment. We're witnessing similar patterns of disruption and possibility, with progressive victories like Mamdani's representing just one manifestation of a broader cultural shift. The prediction of a new party emerging from the ashes of the old isn't political speculation—it's a reflection of what America desperately needs now.

But what might that party represent? And who is it for?

The democratic socialist movement—still largely misunderstood or maligned in mainstream political discourse—has slowly emerged as the most honest response to our compounding crises. Climate collapse, obscene wealth inequality, housing scarcity, racial injustice, debt peonage, and the erosion of labor rights have exposed the rot at the heart of American neoliberalism. It’s no longer fringe to say that capitalism in its current form is unsustainable. What was once relegated to protest chants and graduate seminars is now entering school board meetings and city council races.

In this light, democratic socialism isn’t just an economic orientation—it’s a moral repositioning. A collective reimagining of what dignity looks like when it’s decoupled from productivity. It asks: what kind of society invests in its people not as workers, but as humans? How do we organize resources so that housing, healthcare, education, and even leisure are not privileges of the few, but the inheritance of all?

We’ve seen the outlines of this before—during FDR’s New Deal era, in the Civil Rights Movement, in the demands of labor unions that once defined the American middle class. But those gains were always partial, always racialized, always situated within a larger system of extraction. The promise of democratic socialism today is not only economic redistribution, but a more honest reckoning with history—a politics of repair.

And like 1968, this moment feels charged not just with unrest, but with creativity. Mutual aid networks exploded during the pandemic. Organized labor has regained public support—with 71% of Americans now expressing approval of unions, the highest level since 1965. The success of candidates like Summer Lee, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and now Zohran Mamdani suggests that a coalition is forming—not fast enough to seize power, perhaps, but rooted enough to shift the terms of the conversation.

Of course, this movement is still fragile. Corporate power remains vast, tech monopolies continue to algorithmically shape public opinion, and the Democratic Party’s centrist establishment has proven resilient. But something is changing. There’s an intergenerational impatience. A refusal to wait for the arc of the moral universe to bend on its own.

Where 1968 revealed the limits of reform without revolution, 2025 may offer a chance to recalibrate—not through violence or collapse, but through imagination and solidarity. Not everyone will call it democratic socialism. Some will call it common sense. Others will call it care.

Whatever we name it, the sea change is already underway. The question is whether we will rise with it—or cling to the debris of a system that was never built to carry us all.

The Colonizer's Dilemma

What struck me most during this recent trip wasn’t just the beauty of the architecture or the slowness of a long meal—it was the ambient disconnection. In France and Spain especially, it was harder to find strong, consistent wifi than I’d anticipated. At first, I found this frustrating—my American reflex was to assume connectivity as a given. But over time, it started to feel like something else: a subtle boundary. I noticed people looking at each other instead of their phones. Conversations lingered longer. There was a kind of ambient attention that felt rare back home.

Of course, this isn’t entirely coincidental. The European Union has some of the strictest data privacy regulations in the world. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enacted in 2018, was a landmark shift that redefined how companies could collect and use data. Since then, over €4 billion in fines have been issued across member states for violations. These laws don’t just shape corporate behavior—they subtly shape culture. They send a signal: personal data is not just another commodity.

And yet, even with these protections in place, I couldn’t help but notice how much of America’s digital logic still bleeds through. Meta and Google still dominate online advertising markets in Europe. American apps still line the home screens of teenagers in the UK and Spain. English—specifically, American English—permeates everything from TikTok captions to digital marketing copy. Despite meaningful efforts to push back, the gravity of U.S. tech infrastructure remains strong.

It made me wonder whether connectivity has become one of our most effective exports—not just in a practical sense, but ideologically. We often talk about global capitalism in terms of trade agreements or military spending, but there’s another layer: the psychological and behavioral infrastructure embedded in our technology. What does it mean that the same platforms that optimize our shopping, dating, and news consumption are shaping the attention economies of cities that once prioritized slower, more communal life rhythms?

I don’t have a definitive answer. But as I moved through countries with stronger public welfare systems, more robust healthcare, and walkable urban design, I kept coming back to the same question: can those values hold up under the weight of algorithmic life? Or will they, too, be softened, reshaped, and eventually flattened into the logic of scale, speed, and seamless consumption?

The Design of Political Imagination

Mamdani's success can be partly attributed to the design system deployed in his campaign—specifically, how it engaged the imagination. Design is always political. It’s never just about aesthetics; it shapes how we perceive value, possibility, and belonging. This truth landed more fully for me after visiting the Christian Dior gallery in Paris. Walking through decades of meticulously crafted garments, it became clear how design systems like fast fashion have not only transformed popular aesthetics—they’ve eroded the credibility of skilled craftspeople and reduced cultural labor to disposable trend cycles.

What struck me most, however, was not just the clothes or their beauty, but what they represented. Fashion, art, and music are among the few human languages that transcend borders. They unite us not through policy or capital, but through feeling, memory, ritual. The jobs of makers—designers, artists, musicians, craftspeople—represent real careers with deep civic and spiritual value, even without the reliable golden handcuffs of corporate employment. And yet, our current system persistently devalues them, while elevating those who manage supply chains or manipulate metrics. The irony worth noting: the hands that make are worth less than the hands that scale.

This tension between mass production and artisanal craft is more than aesthetic—it reflects a civilizational fault line between meaning and optimization. It’s visible in the transatlantic contrast between how goods are sourced, sold, and valued. In the European Union, where the “Made In” label still carries cultural capital, quality and craftsmanship remain central to brand identity. A 2023 McKinsey report notes that 64% of EU consumers are willing to pay more for items labeled “locally made” or “crafted.” In contrast, only 37% of U.S. consumers reported the same, with price and speed consistently outranking origin or method of production.

The EU has actively supported small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) involved in artisanal production—offering subsidies, protected designation statuses (like Made in Italy or Denominazione di Origine Protetta), and tax incentives to preserve heritage. In Italy alone, 95% of fashion-related businesses are SMEs, and many still operate on intergenerational knowledge. These businesses don’t just produce garments—they sustain local economies and cultural memory.

Compare this to the U.S., where supply chains are engineered for volume, not meaning. Here, brand manufacturers have largely outsourced production to low-wage economies—China, Vietnam, Bangladesh—prioritizing cost minimization and speed-to-market. According to the American Apparel & Footwear Association, over 97% of apparel sold in the U.S. is imported, and the average American buys over 68 garments a year, most worn only 7 to 10 times before being discarded.

In Europe, retail sell-through models emphasize curation, seasonality, and longer product life cycles. Many luxury boutiques and department stores still buy inventory outright from brand manufacturers, taking on risk in exchange for brand alignment and craft integrity. Meanwhile, in the U.S., the dominant model is consignment or wholesale distribution at volume, often leading to excess stock, aggressive markdowns, and eventual landfill.

My travels reaffirmed this. In Paris, I watched local shoppers browse deliberately, feeling fabrics, inspecting stitching, asking about provenance. People still take pride in owning something made in Italy or crafted in Spain. There’s a ritual to dressing that has not yet been fully severed. In the U.S., meanwhile, the dominant logic is categorization—"cottagecore," "Y2K," "clean girl"—as if identity is a filter one applies rather than a practice one cultivates. Dressing becomes performance for the algorithm, not ritual for the self.

And in this vacuum of meaning, the rise of AI-generated content—fashion, art, music—feels especially hollow. When algorithms remix surface aesthetics without any lived context, we lose something irreplaceable: the depth of culture formed through lineage, struggle, and creative joy. Humans have always been a remix species, but we’ve also always been creatures of ritual and mastery. You can’t download the kind of devotion that goes into a hand-stitched collar or a brushstroke that outlives its century.

Standing in the Louvre, watching thousands of people wait patiently to see the Mona Lisa, I was reminded of art's enduring power to unify us—not through efficiency or optimization, but through awe. Da Vinci didn’t create for virality. He created to reveal. There’s a lesson in that, one we forget each time we reduce culture to commodity.

Fashion is the fascia of society—the connective tissue of our collective aesthetic consciousness. And when we treat it as disposable, we sever a key line to who we are, and who we could become.

The Flatness Fallacy

This brings me to a heated design debate I once witnessed at Yahoo! about visual systems—specifically, whether skeuomorphic or flat graphics better conveyed modernity. Predictably, the graphic designers championed flatness. It was said to reduce "cognitive load," streamline code, modernize the brand. We created elegant rationales for our preferences, as if a more abstract aesthetic inherently offered a higher order of clarity or user empowerment.

But if I’m being honest, we weren’t solving a real problem. We were reverse engineering arguments to validate what we’d already built. The shift to flat design wasn't about the user—it was about us. About looking current. About performing relevance. And behind the jargon and design decks was a deeper truth: humans are metabolically wired to seek ease. We’re lazy by design. Acknowledging this doesn’t insult our intelligence—it clarifies the ways we habitually confuse visual polish with critical thought.

Designers, in this sense, become unknowing accomplices in the manipulation of truth. When something is beautifully designed, we’re more inclined to believe it, trust it, pay for it. This is the aesthetic fallacy: if it looks right, it must be right. It’s why a startup with an elegant landing page can raise millions with a half-formed product, while a scrappy but impactful local initiative might never scale. It’s why conspiracy theorists with professional-grade visuals gain more traction than grassroots educators armed with facts.

Design systems, while useful, are often shortcuts to credibility. A clean interface can become a form of intellectual laundering—flattening nuance, smoothing over contradictions, and giving the illusion of coherence where there may be none. In a world obsessed with frictionlessness, we’ve equated legibility with truth, and modular consistency with integrity. But truth rarely comes packaged neatly.

Take Craigslist. It’s arguably one of the ugliest high-traffic sites on the web. Its design is anti-aesthetic, almost defiant in its refusal to modernize. And yet it remains a vital digital utility because it solves a human problem—connecting people—without posturing. Similarly, many of the most-read blogs, forums, and Substacks are not “well-designed” by Silicon Valley standards. They’re text-heavy, nonlinear, idiosyncratic. But their content has resonance. Their voice cuts through. Their power lies not in their typography but in their perspective.

The internet itself was never designed to be beautiful. It was designed to be useful, then adapted to become addictive. Somewhere along the way, design became a tool of seduction more than service.

And that’s the dilemma: design can either illuminate or obscure. It can invite deeper thought or lull us into passive consumption. Too often, the latter prevails. When attention is the economy, design becomes optimization—not for understanding, but for engagement. And that’s how we end up with flattening metaphors not just on screen, but in thought: "user journey," "conversion funnel," "onboarding experience." Human complexity is reduced to metrics and flows. The designer becomes the accomplice not only to capitalism, but to the erosion of interpretive depth.

Meanwhile, music and the fine arts continue to operate on a different plane. They reflect the zeitgeist not through simplicity but through dissonance, paradox, layered meaning. They are not optimized—they are interpreted. A song or a painting can hold contradictions in a way a button never can. Art, unlike most digital products, doesn’t demand to be understood at first glance. It invites, it lingers, it resists being flattened.

That’s why art and music remain the fastest interpreters of the cultural now—often faster than journalism or policy. While media struggles to translate fact into trust, art slips into the bloodstream. It bypasses our defenses. It moves.

Design could do this too. But it would require us to resist the pressure to package every message for mass adoption. It would mean creating friction intentionally. It would mean allowing systems to feel incomplete if completion would be a lie.

When done with integrity, design can do more than perform credibility—it can reflect collective memory, signal belonging, and redistribute trust. Mamdani’s campaign, developed in collaboration with the design studio Forge, offered one of the clearest counterexamples to the design-as-deception trend I’ve seen in recent years.

Rather than chasing slickness or Silicon Valley minimalism, Forge built a visual system rooted in the existing visual grammar of New York City’s public infrastructure—the bold color palettes of subways, sanitation trucks, public housing signage. This wasn’t a nostalgic nod to civic aesthetics. It was a deliberate design choice that met people where they already were, signaling that Mamdani’s platform didn’t exist outside the system—it existed for it, with it, and within it.

This design strategy quietly echoed the seven cooperative principles defined by the International Cooperative Alliance: democratic member control, autonomy and independence, education and training, cooperation among cooperatives, and concern for community. These are not aesthetic guidelines—they’re structural ethics. And yet, Forge managed to infuse them into visual form: the design looked democratic because it was democratic. It reflected public ownership and common identity. It wasn’t about polish—it was about presence.

Young people, many of whom are daily users of public systems—transit, public housing, public schools—immediately recognized the language. It didn’t require explanation or marketing spin. It resonated. In an era when most political campaigns try to brand like startups, Mamdani’s team branded like a neighborhood—a coalition, not a company.

This is what’s so often missing in the way design is deployed today. Systems are built to flatten nuance rather than lift it. But Forge’s work proved the opposite: that design can deepen recognition, foster allegiance, and reframe what legitimacy looks like. It reminded me that when you design with the community instead of for it, you don’t need to manufacture trust—it already exists.

Compare that with the hyper-designed interfaces of tech platforms, many of which rely on “flat” design to suggest neutrality, when in fact they are anything but. These surfaces are loaded—bias wrapped in Amazon Ember or [insert corporate typeface]. They optimize for belief, not understanding. And users often buy into the sleekness without questioning what lies beneath.

So much of what we now call design is merely aesthetic strategy—a means to sell familiarity, smooth complexity, and mimic integrity. But as Mamdani’s campaign showed, real design is not what is most seamless. It is what is most contextual. Most public. Most human.

When we center design in cooperative values—values that ask us to consider equity, education, interdependence—we start to see design not as a wrapper, but as a structure of meaning. Not just what a campaign or a product looks like, but what it signals about who it serves.

The Danger of Simplified Visualizations

When I encounter graphics like the Pace Layering diagram from The Clock of the Long Now, I’m reminded why I’ve long resisted the influencer talk circuit. These types of diagrams—while clean, intuitive, and seemingly explanatory—are often misleading. They flatten complexity into digestible narratives that feel true, even when they’re not. The Pace Layering model, for instance, attempts to explain how societal systems move at varying speeds—fashion quickly, governance slowly—but it ignores the feedback loops, ruptures, and tensions that define real change. It reduces cultural metabolism to a linear staircase. And when well-meaning people treat such diagrams as gospel, they risk adopting a worldview that is tidy, but wrong.

This is the danger of simplified visualizations: they offer the illusion of insight while bypassing the hard work of understanding. They give us cognitive comfort in exchange for critical engagement. We forget that every diagram is a metaphor, not a map. Every model omits what doesn’t fit. And in an age where speed and shareability dominate, these shortcuts can do real harm—especially when used to teach, to inspire, or to strategize.

Design, ultimately, is the work of creating shortcuts—of shaping perception, smoothing edges, lowering friction. It permeates behavior at every level. From how we swipe and tap to how we think and move through public space, design conditions our choices before we realize we’ve made them. UX systems train us to expect immediate gratification. Branding trains us to associate aesthetics with trust. Interface hierarchies train us where to look and what to ignore. Over time, these patterns don’t just reflect our habits—they become them.

And nowhere is this more visible than in fashion. Fashion doesn’t merely respond to culture—it records its loss. The death of traditional crafts, the rise of synthetic fabrics, the dominance of algorithmically shaped trends all tell a story about what we no longer hold sacred. When culture is thriving, clothing is rich with meaning—ritualistic, geographic, intergenerational. What we wear signals who we are, where we come from, what we value. But in the age of fast fashion, clothing becomes disposable costume. A rotating performance of identity dictated by market trends, TikTok aesthetics, and micro-seasonal drops.

Fashion once followed lived context—ceremony, climate, material availability, regional silhouettes. Now it follows data. The top 10 search terms from one week become a clothing line the next. What was once made to last is now made to signal. What was once embedded with memory is now produced to be discarded. This is not just an environmental disaster—it is a cultural one.

The simplification of visual systems, then, is not confined to diagrams and dashboards. It is visible in the very fabrics we wrap around ourselves. When we wear garments stripped of story, when we prize trend over textile, we participate—often unknowingly—in the erasure of tradition. Fashion becomes a literal expression of flattened culture.

And yet, this loss is not inevitable. It is designed. Just as diagrams like Pace Layering omit complexity for the sake of legibility, so too do global supply chains omit tradition for the sake of efficiency. Both are driven by the same logic: simplify to scale. But when we scale too far, we forget what we’re scaling from. The scaffolding of meaning collapses under the weight of optimization.

If design is to serve us in this moment, it must be willing to resist simplification. It must invite us back into contradiction, into texture, into histories that don’t fit neatly onto slides or into checkout flows. It must help us remember—not just where we’re going, but what we’ve lost on the way.

And yet, amidst the sea of homogenized, algorithm-fed fashion, I encountered something unexpected during my travels: a quiet return to craft. At several retailers across France and Spain—some boutique, some chain—I saw racks of garments featuring handmade embroidery, hand-stitched linen, and lace eyelet blouses with an attention to detail that felt out of sync with the globalized fashion cycle. These weren’t ostentatious pieces. They were modest, wearable, and beautifully made. Dresses with scalloped hems, seams that told of human hands rather than factory templates. I normally have no real interest in lace—it has always read too delicate, too ornamental for my sensibilities—but in the oppressive heat and humidity, these garments made sense. They were breathable, functional, durable. They carried purpose and they were stylish. Instantly elevated and more presentable.

This is what struck me most: the materials themselves told a story not just of aesthetics, but of climate, geography, and tradition. These were textiles shaped by the needs of the body and the rhythms of a place—not by trend cycles or TikTok cores. Linen that softens with wear. Eyelets that allow air to pass through. Embroidery that hints at heritage, even if anonymous. In these pieces, I felt a kind of resistance to the global monoculture of fashion. A reminder that design begins with care: for the wearer, for the maker, for the material.

It made me think about how disconnected so much of American clothing has become from climate, from context, from touch. Our fashion is largely synthetic and sweat-inducing, optimized for price points and aesthetics that photograph well but wear poorly. Polyester doesn’t breathe. Nylon traps heat. And yet these are the materials most mass-market American brands continue to use—because they serve the bottom line.

This is where the real loss of culture becomes visible. In texture. In fabric. In how something feels on a hot day. We’ve traded durability for disposability, tradition for trend responsiveness, breathability for sheen. And most of us don’t even notice—because we've been taught not to feel the difference.

But standing in those shops, touching garments that bore the imprint of human labor and intentional design, I did notice. I remembered. And I wondered how much wisdom we’ve forgotten in the name of convenience.

Time, Metrics, and Maturity

Touching those garments—feeling the breathability of linen, the softness of hand-finished hems—I was reminded how design, when rooted in material intelligence and cultural memory, slows us down. It invites us to notice. To care. To sense time differently—not as a resource to extract, but as a rhythm to align with. These pieces weren’t just about aesthetics; they were about durability over disposability, patience over production. They resisted the tyranny of speed.

Which brings me to time itself—something we rarely understand, even as we’re governed by it. Many people talk about metrics as if they exist in a vacuum: quarterly returns, weekly KPIs, minutes saved by an app. But these measurements flatten time into performance units, stripping away scale, memory, and ritual. Time, in its real form, isn’t so obedient. It doesn’t accommodate our ambition or urgency. It unfolds unevenly—through seasons, through bodies, through generations.

There’s an old adage that youth is wasted on the young. And while that may carry some truth, I’ve come to believe that maturity—real maturity—is best served in a practiced body. In my twenties, I could dance until sunrise, smoke through my stress, show up and do it again. I thought endurance was vitality. But now, I understand something quieter: that endurance without purpose is just another form of dissociation. With what a seasoned raver might call “legend energy,” I’ve learned to pay attention to how and where time moves through me.

And that’s what politics—real politics—can help us remember.

Politics is not just about policy. At its best, it’s about shaping the conditions through which we experience time itself. Do we have time to rest? To heal? To learn? To grieve? Do we have a sense of future we can plan for, or are we caught in the churn of surviving the next billing cycle, election, algorithmic shift?

Under capitalism, time is relentlessly monetized. Under white supremacy, it is unevenly distributed. Under patriarchy, it is stolen—from caregivers, from mothers, from the aging. But under a truly democratic political vision—one rooted in care, cooperation, and collective sovereignty—time can be reclaimed as something more sacred. Not a scarcity to hoard, but a commons to share.

This is why campaigns like Mamdani’s feel so alive. They aren’t just promising new outcomes—they’re offering new temporalities. A slower, more just pace of governance. A future that doesn’t just accelerate what is, but interrupts it. Makes room. Reroutes. In that sense, politics becomes not just a response to crisis, but a cultural technology for reimagining our relationship to time itself.

And that, perhaps more than any policy proposal, is the revolution we need now.

The Sacred Refusal and What Comes Next

In my previous essay, I wrote about The Sacred Refusal—the slow, often invisible split between our deeper values and the capitalist machinery we’ve been conditioned to serve. That refusal continues to spread, branching into movements, campaigns, and subcultures that challenge the inevitability of extraction-as-progress. Zohran Mamdani’s recent success is a signal that many of us are ready to abandon the tired binary of left vs. right in favor of something deeper: a reclamation of meaning, care, and collective authorship.

Progressivism, in its truest form, requires sacrifice. And yet many former progressives have chosen comfort over conviction, becoming bureaucrats of the very system they once opposed—opting into careerism’s creature comforts while authoritarianism rebrands itself as middle-class empowerment. The battle ahead won’t be won through televised debates or legacy media headlines. It will require an opposition that moves nimbly, often in shadow, building power beneath the radar while leveraging new tools to reach the people who still believe in dignity, equity, and shared destiny.

Young people today feel this. Despite the noise, despite the cruelty, they carry a soft power—an emotional intelligence hardened by crisis and cultivated in community. They are not naïve. They understand, more clearly than any previous generation, that a billionaire class shouldn’t exist. That systems built on hoarding and harm cannot be redeemed. That transformation will require both precision and poetry.

And this is where the makers come in—the artists, musicians, designers, craftspeople. The ones who traffic not in metrics, but in meaning. While corporate workers chase conversions and commissions, it’s the makers who carve out the cultural memory needed to imagine something better. Their work forms the aesthetic language of possibility. A counterculture of one-offs, couture, and highly personal creations isn’t just a stylistic choice—it’s a spiritual one. A refusal to mass-produce what should remain sacred.

To support a maker over a machine, to choose ritual over speed, is to participate in resistance. It’s not anti-progress—it’s rehumanized progress. It’s an assertion that the future isn’t something we scale into existence, but something we shape through depth, slowness, and care.

This sea change—political, cultural, emotional—may be the most significant of our lifetime. Like The Beatles’ irreverent take on American patriotism, it comes disguised as parody, but functions as prophecy. “Back in the U.S.S.R.” mocked nationalistic bravado even as it revealed its staying power. In a similar way, we find ourselves now—Back in the USSA—staring into the mirror of empire once again, only to realize that parody has become premise. The joke, perhaps, is on us. But that doesn’t mean we can’t rewrite the ending.

We are not what we appear to be—and that’s where the transformation begins.

We may use AI to augment our processes, and yes, it might one day replace the keyboard. But to suggest it will replace us—our lived experience, our intuition, our cultural memory—is not only shortsighted, it’s a betrayal of the very intelligence that brought us here. The future belongs to those who know how to wield tools, not worship them. To those who can hold technological fluency and human depth in the same hand.

The sacred refusal is alive. It hums beneath the systems we are told we must maintain. It gathers in quiet rooms, in protest chants, in late-night sewing circles, in soundproof studios and unfunded campaigns. It builds not in volume, but in vibration. Not in spectacle, but in resonance.

The song may be stuck in my head—but maybe that’s the point. A single melody, looped and misunderstood, that charts the dissonance of empire and sets the stage for something else. Something we can feel but haven’t yet named.

And if we’re listening closely—if we’re making carefully—we’ll hear it: the opening notes of a revolution played with breath.